In the second movement, The Story of the Kalendar Prince, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote two extended bassoon solos.

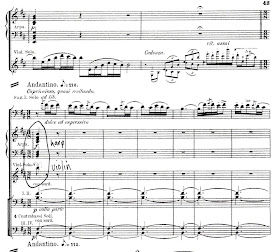

The first solo comes at the beginning of the movement, right after the violin cadenza with harp accompaniment.

In order to form an interpretation of this solo which capitalizes on its expressive possibilities in such a way that the listener can fully appreciate them, an understanding of the solo's orchestral context is essential.

The Beginning

- The bassoon solo starts right after the violinist finishes on a very high note.

- The harp rolls a full chord on the downbeat of the measure in which you enter.

Therefore, it's helpful and expressively important to start with a full, resonant tone -- including the G grace note. I believe the phrase should relax in intensity to the B in bar three, so starting with a full sound also gives you a better chance for an expressive shape to the opening bars. In this solo, "Up is Up and Down is Down"* is a good maxim.

The Middle

By following the bass parts above, you can see that the harmonic motion is static for several bars. Notice where the chord changes occur (circled). By broadening at these points, you can enhance the new harmony underneath and allow the music to breathe. Breathe literally, too, as these chord changes happen near traditional breathing points for the bassoonist.

In order to bring out the seamless quality of this musical story telling, I strive to make my breathing as unobtrusive as possible. The phrases are like a chapters you weave together into a story in order to keep the constant attention of the listener.

Thus, when you do breathe, try to leave the last note before the breath with a rounded, resonant tone, breathe quickly and re-enter at the same intensity at which you left the sound. It helps to broaden a bit just before breathing. This buys you time for the breath without adding the perception that you've added beats to the measure.

The End

Knowledge of the context becomes most important when finishing this solo. There is a lot going on in the last few bars. By two bars before A I've reached the most expressive, fullest sound in the solo. In the next bar I begin the process of handing the solo off to the oboe.

The conductor re-enters the picture at this point to assist in the hand off. The ritard assai, along with serving an expressive function, gives the conductor and everyone who enters at A a chance to get ready to play.

Therefore, the D dotted 16th note in the last bar of the solo (last circled beat above) becomes the pivot point from one section to the next. This may be the longest dotted 16th note in the literature!!

You will see two beats from the conductor during this little note! One beat when you first play it to help the uppermost bass line move with you, and another to help you move from it to the C# and to give a pick up to those that enter at A.

Because the next section is in strict time and no longer flexible, the last two notes of the solo must be played in the NEW tempo: ♪=112. The need for the conductor and other musicians to start predictably

takes away any freedom you have here. In effect, the ritard assai only applies up to the famous D dotted 16th note.

Played as an Excerpt

In order to play this passage convincingly as an excerpt (in an audition, for instance), the performer must play with a sense that there is an imaginary conductor and orchestra in accompaniment. Younger, less experienced players who show their understanding of the context of this solo when performing it can ease the minds of those listening who may otherwise question their slim resumes and lack of experience.

Coming Next

In my next post, I'll examine the context of the three bassoon cadenzas that follow later in the movement.

* An expression used by oboist, John Mack to indicate phrasing in which a higher pitch is more intense than a lower one.