Verdi's Requiem or a Test of Flexibility

We finished our season last weekend with two performances of the Verdi Requiem. I still have the sounds of the

Dies Irae ringing in my head!

I'd like to use this piece as a point of departure for the topic of flexibility in performance.

For the bassoonist, the

Requiem features many wonderful passages, including a long obbligato part for 1st bassoon in the

Quid Sum Miser section of the

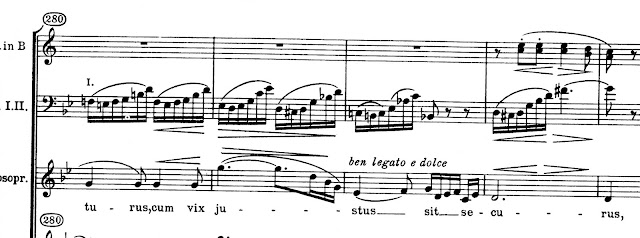

Dies Irae (the second movement of the piece). Below is the 1st bassoon part for that section:

A quick perusal of the part reveals a steady, but tortuous series of 16th notes with a hairpin under many of the groups of six. You can see cues for 2 clarinets before the solo starts and some cues for the Soprano during rests, so there are some other things going on during this. The end of one measure has the marking,

"col canto", so something interesting must happen there.

However, aside from these little clues it's hard to view this solo as anything other than a very long, steady stream of 16ths -- a rhythm that's nearly constant throughout.

This would lead you to practice it that way, certainly, to make sure that the legato is smooth and the fingers are very accurate and even.

A look at the score shows that Soprano, Mezzo and Tenor soloists are singing during this passage, but their lines look smooth -- mostly eighths and quarters. Very little to get in the way of a steady flow.

Then comes the first rehearsal and all bets are off!

The conductor starts the section at one tempo, you come in and play in time with the beat. The mezzo enters at a different tempo and stays that way. You have to adjust, suddenly slowing down. Nearly losing your place, you drop a phrase trying to follow her and the conductor has a spasm in order to follow her as well.

Just as the new tempo settles in you approach a cadence and the mezzo needs a breath. She appears to come to a near halt in the middle of bar 282 for the breath and takes her time with the 16ths that follow. The two eighth rests in your part seem to last for ever and you're tempted to enter early, interrupting her 16ths.

At this point, you're wary that there will be more interruptions in the steady flow of the rhythm and are watching the conductor like a hawk and trying to listen for the soloists in order to stay on track.

You may be tempted to put down the bassoon and intone the first words of the section which are, "What can a miserable wretch like me say?"

Something like this happened this week in the rehearsals, although not so dramatically. John Clouser played the 1st bassoon part (beautifully, by the way!) and this is what I've experienced when I've played the 1st bassoon part as well.

Hope For the Best, But Prepare For the Worst

Well, maybe things aren't really

that bad, but this motto is a good way to approach the preparation of a major solo in orchestral repertoire!

After lots of careful practice, some listening and score study, come to the first rehearsal with a fully-formed interpretation of a solo or major part and execute it that way.

I think conductors and others -- whether they admit it or not -- like it when others take responsibility for music making in this way. They don't have to spend precious rehearsal time spoon feeding you their interpretation. Besides, you may hate the way they want it to go!

Of course, they may have (and often do) have something to say after you've played it through, but that's to be expected, isn't it?! As Arnold Jacobs, the former tuba player for the Chicago Symphony used to say,

"It's better to have something to disagree with than to have nothing to talk about."

The Maitre D'

I like to imagine orchestral musicians as wine experts or the wait staff in a Zagat-rated gourmet restaurant. You know what your regular clientele like to order, where they like to sit, how to pace the service to make their dining experience most enjoyable, etc. You start with these assumptions, developed over years of experience.

However, occasionally there will be a day when Mr. X doesn't want his usual pre-dinner martini. Instead, tonight he wants to try something different. What would you recommend, knowing his tastes?

While not a mind reader, a good waiter can make an educated guess as to what to offer.

Tips For Preparation

These surprises can be rehearsed in your preparation. As I said above, no one can read minds, but, after playing for a conductor for a period of years, you should have a mental file on his/her tempo choices, musical ideas, etc. You can try these out in practice sessions leading up to the first rehearsal.

In the case of the Verdi, the rubatos and breathing of the singers is well documented in recordings. Listening to a few can help you be ready for tempo curve balls.

When preparing for an audition, sometimes it's helpful to play the excerpts in ways that you don't actually agree with to build flexibility. Sometimes, being asked to play an excerpt again with a different, dictated approach is the way a committee uses to break an impasse in their voting.

I know I won a job once by the way I played a solo in the first movement of Shostakovich Symphony #1.

Willard Elliot told me that in the final round of his Chicago Symphony audition he was asked to perform the Bolero solo at quarter=63 (much slower than usual). His success in this helped put him over the top.

During the Rehearsal/Performance

These curve balls are thrown during a rehearsal or even a performance. Things happen and you have to adjust.

Building in flexibility during practice (becoming comfortable with different tempos, interpretations, etc.) can help you adjust in the moment. Have a friend ask you to play a passage very differently from the usual way to see how you adjust. Is there a way of playing it that keeps some of your ideas intact while incorporating the new ones?

In addition, try not to get locked into one way of gathering instant feedback for yourself while playing, i.e., by just watching the conductor. Often they are as frazzled as you are when a soloist strays from the tempo in a performance.

I try to take in a measure or so of music at a time and look up so I can see what's going on on and around the podium, looking down when I need more music to continue. Kind of like a swimmer coming up for air during the stroke. A good short term memory is helpful!

During an audition once a conductor came up on stage and conducted me in the Firebird

Berceuse. It was just the two of us there, so why was he doing this? I guessed it was because he wanted to see if I could follow his non-verbal instructions. I played the solo from memory, looking at him the whole time. Sure enough, he did give me some instructions with his gestures which I tried to incorporate in my performance. Again, maybe it wasn't how I would have executed the solo, but I had to put those assumptions aside and show flexibility. I won that job, too.

Your knowledge of what else is going on in the score really can come to your aid when the unexpected happens .

Do you know the solo part well enough to accompany it without the help of the conductor?

If you can't see/hear the soloist, can you position yourself a little better? If not, are there others playing on whom you can guide?

These are some of the resources available to you for survival and success in a tough situation.

*Note to bassoonists reading this: You may have noticed in the scanned part above that there are several misprints in the Peters edition of this piece in the part, including three wrong pitches! Consult the score before learning this part. Excerpt books also have some minor discrepancies.