We performed Ravel's Rapsodie Espagnole last month at the Blossom Music Center.

I'd like to devote this post to the cadenza for two bassoons in the first movement.

The movement title is Prélude à la nuit or Prelude to the Night. The movement is full of impressionistic effects for the orchestra that hint at night sounds in Spanish town. Perhaps the two bassoons are mysterious gusts of wind blowing dust down a deserted street in the early hours of the morning.

Aside from the virtuoso writing and the use of non-traditional harmonies, it is notable that there is no meter throughout this cadenza.

Sometimes this passage is played in a steady tempo. I think this decision constitutes a major missed opportunity to add to the impressionistic character of this section. The lack of meter should indicate to the performers that some freedom is intended with the pulse. It's a shame to hear this duet played like an etude! It makes me wonder if the two players communicate so poorly that they found it necessary to play it steadily so as to keep their place!

Regarding pulse, I think it's important to utilize what's on the page when deciding how to make the notes play out over time.

Notice where there are fermatas and where there are none.

Three quarter notes, but only two fermatas, so don't sit on the first quarter note B too long!

Begin an accelerando after the second hold when the sextuplets start up again. It's best to reach a steady pulse at the height of the crescendo (second bassoon has a difficult part starting here). Decrease speed as you diminuendo.

The measure before Number 9 is often played steadily, too. There is still no meter to hem you in and the indication is Très ralentir, so it's hard to understand why the sextuplet 8th notes should be steady as a rock!

As you approach the hold a broadening of the pulse goes naturally with the crescendo.

What to Expect from the Conductor

This is a very touchy passage for both players and a good conductor will mostly stay out of the way, helping only when necessary -- at the beginning and the end.

If you want it to stay that way, it's extremely important that the two players run through the passage separately as many times as necessary so it goes off predictably well in the first run-through. If trouble happens, conductors have a hard time resisting the urge to "help". You may then have to play it in a way that is quite foreign to your understanding and more difficult than necessary.

Ideally, the conductor should give a cue for starting the first note and then help with getting out of the fermata at the end just before Number 9 and that's it!

How to Lead

If you are playing first bassoon on this, you will need to sharpen your skill in leading. Below, I've marked in red where cues should be given.

Hold still for the long, held notes. Cues 3-5 could be given as steady beat in a moderate tempo. In this way, the 32nd note flourish will sound faster than the 16th note sextuplets at the beginning.

To help the accelerando start slowly, I recommend cuing the E# in the first set, then just cuing the first of each group. The Très ralentir bar can be cued in differnt ways, but the method outlined above works as well as any other one.

The very end may be taken care of by the conductor. If so, you will see one of two possible ways to end this.

1. A cue for the last quarter beat before Number 9 and a downbeat at 9.

2. A cue for the last quarter and one for the last note before 9 and then a downbeat.

How to give cues

Try to give cues using as little body language as necessary. It sends a bad signal to your second bassoonist if you are swinging your bassoon on the beats like a baseball bat! Sensitive players can pick up on small motions using peripheral vision. Just a slight motion is necessary. Be careful to be still when not cuing to avoid confusion!

Use in an audition

This excerpt is commonly used in the final round of a second bassoon audition. It often involves the candidates playing it with the Principal Bassoonist. If you find yourself in this situation, remember that it's very unlikely that any of the candidates will play this perfectly together with the Principal the first time through.

The real test comes in the second try, when you can show how much you picked up on during the first run-through. It is fine to ask a question or two, if necessary before playing it again, but don't get involved in any intellectual discussions at this point!

A fingering

If you have trouble with the slur from the high C# to G# at the first hold, try this fingering for the G#.

Showing posts with label Auditions. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Auditions. Show all posts

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Rapsodie Espagnole -- the cadenza

We performed Ravel's Rapsodie Espagnole last month at the Blossom Music Center.

I'd like to devote this post to the cadenza for two bassoons in the first movement.

The movement title is Prélude à la nuit or Prelude to the Night. The movement is full of impressionistic effects for the orchestra that hint at night sounds in Spanish town. Perhaps the two bassoons are mysterious gusts of wind blowing dust down a deserted street in the early hours of the morning.

Aside from the virtuoso writing and the use of non-traditional harmonies, it is notable that there is no meter throughout this cadenza.

Sometimes this passage is played in a steady tempo. I think this decision constitutes a major missed opportunity to add to the impressionistic character of this section. The lack of meter should indicate to the performers that some freedom is intended with the pulse. It's a shame to hear this duet played like an etude! It makes me wonder if the two players communicate so poorly that they found it necessary to play it steadily so as to keep their place!

Regarding pulse, I think it's important to utilize what's on the page when deciding how to make the notes play out over time.

Notice where there are fermatas and where there are none.

Three quarter notes, but only two fermatas, so don't sit on the first quarter note B too long!

Begin an accelerando after the second hold when the sextuplets start up again. It's best to reach a steady pulse at the height of the crescendo (second bassoon has a difficult part starting here). Decrease speed as you diminuendo.

The measure before Number 9 is often played steadily, too. There is still no meter to hem you in and the indication is Très ralentir, so it's hard to understand why the sextuplet 8th notes should be steady as a rock!

As you approach the hold a broadening of the pulse goes naturally with the crescendo.

What to Expect from the Conductor

This is a very touchy passage for both players and a good conductor will mostly stay out of the way, helping only when necessary -- at the beginning and the end.

If you want it to stay that way, it's extremely important that the two players run through the passage separately as many times as necessary so it goes off predictably well in the first run-through. If trouble happens, conductors have a hard time resisting the urge to "help". You may then have to play it in a way that is quite foreign to your understanding and more difficult than necessary.

Ideally, the conductor should give a cue for starting the first note and then help with getting out of the fermata at the end just before Number 9 and that's it!

How to Lead

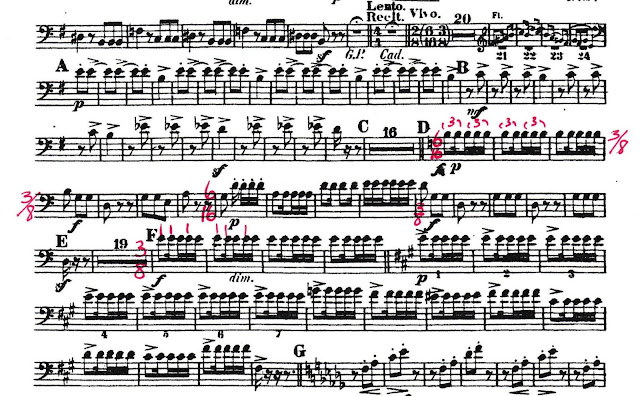

If you are playing first bassoon on this, you will need to sharpen your skill in leading. Below, I've marked in red where cues should be given.

Hold still for the long, held notes. Cues 3-5 could be given as steady beat in a moderate tempo. In this way, the 32nd note flourish will sound faster than the 16th note sextuplets at the beginning.

To help the accelerando start slowly, I recommend cuing the E# in the first set, then just cuing the first of each group. The Très ralentir bar can be cued in differnt ways, but the method outlined above works as well as any other one.

The very end may be taken care of by the conductor. If so, you will see one of two possible ways to end this.

1. A cue for the last quarter beat before Number 9 and a downbeat at 9.

2. A cue for the last quarter and one for the last note before 9 and then a downbeat.

How to give cues

Try to give cues using as little body language as necessary. It sends a bad signal to your second bassoonist if you are swinging your bassoon on the beats like a baseball bat! Sensitive players can pick up on small motions using peripheral vision. Just a slight motion is necessary. Be careful to be still when not cuing to avoid confusion!

Use in an audition

This excerpt is commonly used in the final round of a second bassoon audition. It often involves the candidates playing it with the Principal Bassoonist. If you find yourself in this situation, remember that it's very unlikely that any of the candidates will play this perfectly together with the Principal the first time through.

The real test comes in the second try, when you can show how much you picked up on during the first run-through. It is fine to ask a question or two, if necessary before playing it again, but don't get involved in any intellectual discussions at this point!

A fingering

If you have trouble with the slur from the high C# to G# at the first hold, try this fingering for the G#.

I'd like to devote this post to the cadenza for two bassoons in the first movement.

The movement title is Prélude à la nuit or Prelude to the Night. The movement is full of impressionistic effects for the orchestra that hint at night sounds in Spanish town. Perhaps the two bassoons are mysterious gusts of wind blowing dust down a deserted street in the early hours of the morning.

Aside from the virtuoso writing and the use of non-traditional harmonies, it is notable that there is no meter throughout this cadenza.

Sometimes this passage is played in a steady tempo. I think this decision constitutes a major missed opportunity to add to the impressionistic character of this section. The lack of meter should indicate to the performers that some freedom is intended with the pulse. It's a shame to hear this duet played like an etude! It makes me wonder if the two players communicate so poorly that they found it necessary to play it steadily so as to keep their place!

Regarding pulse, I think it's important to utilize what's on the page when deciding how to make the notes play out over time.

Notice where there are fermatas and where there are none.

Three quarter notes, but only two fermatas, so don't sit on the first quarter note B too long!

Begin an accelerando after the second hold when the sextuplets start up again. It's best to reach a steady pulse at the height of the crescendo (second bassoon has a difficult part starting here). Decrease speed as you diminuendo.

The measure before Number 9 is often played steadily, too. There is still no meter to hem you in and the indication is Très ralentir, so it's hard to understand why the sextuplet 8th notes should be steady as a rock!

As you approach the hold a broadening of the pulse goes naturally with the crescendo.

What to Expect from the Conductor

This is a very touchy passage for both players and a good conductor will mostly stay out of the way, helping only when necessary -- at the beginning and the end.

If you want it to stay that way, it's extremely important that the two players run through the passage separately as many times as necessary so it goes off predictably well in the first run-through. If trouble happens, conductors have a hard time resisting the urge to "help". You may then have to play it in a way that is quite foreign to your understanding and more difficult than necessary.

Ideally, the conductor should give a cue for starting the first note and then help with getting out of the fermata at the end just before Number 9 and that's it!

How to Lead

If you are playing first bassoon on this, you will need to sharpen your skill in leading. Below, I've marked in red where cues should be given.

Hold still for the long, held notes. Cues 3-5 could be given as steady beat in a moderate tempo. In this way, the 32nd note flourish will sound faster than the 16th note sextuplets at the beginning.

To help the accelerando start slowly, I recommend cuing the E# in the first set, then just cuing the first of each group. The Très ralentir bar can be cued in differnt ways, but the method outlined above works as well as any other one.

The very end may be taken care of by the conductor. If so, you will see one of two possible ways to end this.

1. A cue for the last quarter beat before Number 9 and a downbeat at 9.

2. A cue for the last quarter and one for the last note before 9 and then a downbeat.

How to give cues

Try to give cues using as little body language as necessary. It sends a bad signal to your second bassoonist if you are swinging your bassoon on the beats like a baseball bat! Sensitive players can pick up on small motions using peripheral vision. Just a slight motion is necessary. Be careful to be still when not cuing to avoid confusion!

Use in an audition

This excerpt is commonly used in the final round of a second bassoon audition. It often involves the candidates playing it with the Principal Bassoonist. If you find yourself in this situation, remember that it's very unlikely that any of the candidates will play this perfectly together with the Principal the first time through.

The real test comes in the second try, when you can show how much you picked up on during the first run-through. It is fine to ask a question or two, if necessary before playing it again, but don't get involved in any intellectual discussions at this point!

A fingering

If you have trouble with the slur from the high C# to G# at the first hold, try this fingering for the G#.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

Scheherazade -- Technical Matters

Here are some technical solutions I use for some of the difficult passages in the rest of the piece.

First movement, last note

This from a guy who wrote a classic book on orchestration!! High B is certainly one of the most unstable notes on the bassoon. I can put mine anywhere within about a minor third range if I want!

Second bassoon has an E in the staff, so you can tune with that part. However, Clarinet 1 has the B an octave higher (often sharp!). So you need some flexibility with this.

Here are some fingerings to try, especially if you find you are sharp on this note or it sticks out.

Note that neither fingering uses the low Eb key. Try your regular high B fingering without the low Eb key. It may have a better sound!

Octave G's

This passage with the G's might flow better if the upper G's are played with the left index finger completely removed. Watch for cracked articulation, though!

Last movement meter changes

In the last movement comes a section that alternates between three to the bar and two to the bar. Meters represented are 2/8, 3/8 and 6/16. In all cases, the duration of each bar is the same and the section is conducted in one.

Thus, it's just a matter of deciding how each bar is divided up.

The writing is confusing at times and maybe not always correctly written.

I've marked in red where the meter changes. Note: at D the figure should be played as two triplets, whereas at F, the figure is written the same, but the grouping must be three to the bar. Listen to a recording and you'll see what I mean.

First movement, last note

Second bassoon has an E in the staff, so you can tune with that part. However, Clarinet 1 has the B an octave higher (often sharp!). So you need some flexibility with this.

Here are some fingerings to try, especially if you find you are sharp on this note or it sticks out.

Octave G's

This passage with the G's might flow better if the upper G's are played with the left index finger completely removed. Watch for cracked articulation, though!

Last movement meter changes

In the last movement comes a section that alternates between three to the bar and two to the bar. Meters represented are 2/8, 3/8 and 6/16. In all cases, the duration of each bar is the same and the section is conducted in one.

Thus, it's just a matter of deciding how each bar is divided up.

The writing is confusing at times and maybe not always correctly written.

I've marked in red where the meter changes. Note: at D the figure should be played as two triplets, whereas at F, the figure is written the same, but the grouping must be three to the bar. Listen to a recording and you'll see what I mean.

Scheherazade - Cadenzas

Let's look now at the three cadenzas that come later in the movement. From a visual standpoint it's easy to see that each successive cadenza is more elaborate than the previous.

Therefore, it's smart to underplay the first one just a little. Not too long a hold on the F, not too slow to start with, not much accelerando or crescendo.

This leaves room for more of everything in the next two cadenzas. Longer hold on the F, slower start to the triplets, more crescendo and accelerando to the end. Note the ritardando molto at the end of the third cadenza. This can start earlier than indicated if you want -- on the last G and following.

Each cadenza is introduced by the three note sequence, D, E, F in quarter note triplets. I like to provide some direction to this introductory fanfare by playing the D and E as the latter part of a three-note quarter triplet group, giving the two notes a pickup feel as they approach the F. A slight crescendo towards the F in each case is helpful.

In the third cadenza, I use a simplified fingering for the E-D-E triplet alternation which occurs twice.

Adding the right thumb Bb for all three notes will help stabilize the E. Alternatively, adding the low Eb key may be more effective.

I return to a normal, full fingering for E in the next triplet group (D, E, F).

Scheherazade -- Interpretation

In this post, I'll offer some guidelines for interpretation and display an edited version of the bassoon solo from the beginning of the second movement.

Guidelines:

Maybe that's not quite the right word to use for developing an interpretation for this solo, because the musical indications instruct the performer to use some freedom when playing it.

Capriccioso, quasi recitando, dolce espressivo -- all terms dealing with expression are the indications for this solo.

Add to that the simple accompaniment and there's a good amount of room for personal expression in this solo.

In fact, I'm actually a bit hesitant to offer an interpretation for this solo because I've heard many that differ from mine that I really like!

This solo is one of the few heard at auditions in which I can listen a bit more for the individual voice of the performer. I want to know what's in that person's heart when playing this solo.

Nonetheless, I'll venture to offer some suggestions.

1. Don't use excerpt books! They are full of mistakes and edits by people other than the composer. The Scheherazade solo and cadenzas are notoriously badly represented in excerpt books. Except for reference to music which is still not in the public domain there is no reason to use them. IMSLP has made them obsolete. There is now no excuse for bassoonists not to know the score (also available on IMSLP) and have a copy of the complete bassoon part.

2. Given that this solo consists of only seven pitches, other areas besides range must be exploited for expressive riches. Look at vibrato, rubato, added dynamics and implied meters for resources.

3. Be sure to examine intonation. There is no reason that this solo can't be played beautifully in tune! It's easy enough that you can focus on achieving pristine intonation. Matching pitch and tone quality between C# and D is important. Also, be sure that E is supported enough to relate well to F#. Be careful that G and A don't rise in pitch at full volume. Be careful to adjust according to which direction you approach a problem note. If coming to a note with a flat tendency from above it, you will need to keep the support up and not let it go because you are descending, for instance.

OK, here's my interpretation in red below.

In the opening, notice the 2/8 meter implied by the slurred groups. Generally, slurred notes are grouped in such a way as to provide emphasis on the beginning part of the slur, so it's helpful to stress the first 16th in each group. This emphasis (as opposed to stressing the 8th notes) will also help bring out the accents in the next section as the stress gets relocated to the end of the groupings on the 8th notes.

I follow the general rule of phrasing -- "Up is Up and Down is Down" at the outset by allowing each 2/8 group to relax in intensity as the phrase relaxes in pitch to the note B. In general, the places for crescendo are marked, except at the end. What the phrasing needs is a few more places for diminuendo to set the level low again. Otherwise, there are three crescendos in a row (one per line).

In the second line, measure 4 there is a small detail. Many editions have accents over the second E and the F#, but the score shows tenuti, just like those two bars later. I think the tenuti work better here, unifying and simplifying the interpretation.

Many bassoonists play an echo phrase in the second line to add more contrast to the solo. I prefer the echo to start on the second beat of the next to last bar of line 2. This way the echo coincides and reinforces the embellishment of the previous phrase (which starts on the fourth bar of line 2). Compare the last two notes of the 4th bar with the last four notes of the 8th bar of the line and you'll understand my reasoning. Also, then the first phrase and echo are complete phrases and not fragments.

Rubato should play a role in any interpretation of this solo. It's really boring to hear this played steadily at ♪ = 112! Push and pull of tempo can come in line 2 with the tenuto 8ths holding back and the 16ths moving forward slightly. The accented section before it can have a slightly faster tempo if desired as well. All deviations from a steady tempo should be subtle and only be used to reinforce harmonic changes and other expressive ideas.

As I said before, there are many other wonderful interpretations of this solo to be heard in recordings. The Reiner recording with Leonard Sharrow is a great place to start, but also listen to the New York Philharmonic with Yuri Temirkanov (Judy LeClair) and the recordings with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra (Schoenbach, Garfield) for inspiration.

Guidelines:

Maybe that's not quite the right word to use for developing an interpretation for this solo, because the musical indications instruct the performer to use some freedom when playing it.

Add to that the simple accompaniment and there's a good amount of room for personal expression in this solo.

In fact, I'm actually a bit hesitant to offer an interpretation for this solo because I've heard many that differ from mine that I really like!

This solo is one of the few heard at auditions in which I can listen a bit more for the individual voice of the performer. I want to know what's in that person's heart when playing this solo.

Nonetheless, I'll venture to offer some suggestions.

1. Don't use excerpt books! They are full of mistakes and edits by people other than the composer. The Scheherazade solo and cadenzas are notoriously badly represented in excerpt books. Except for reference to music which is still not in the public domain there is no reason to use them. IMSLP has made them obsolete. There is now no excuse for bassoonists not to know the score (also available on IMSLP) and have a copy of the complete bassoon part.

2. Given that this solo consists of only seven pitches, other areas besides range must be exploited for expressive riches. Look at vibrato, rubato, added dynamics and implied meters for resources.

3. Be sure to examine intonation. There is no reason that this solo can't be played beautifully in tune! It's easy enough that you can focus on achieving pristine intonation. Matching pitch and tone quality between C# and D is important. Also, be sure that E is supported enough to relate well to F#. Be careful that G and A don't rise in pitch at full volume. Be careful to adjust according to which direction you approach a problem note. If coming to a note with a flat tendency from above it, you will need to keep the support up and not let it go because you are descending, for instance.

OK, here's my interpretation in red below.

In the opening, notice the 2/8 meter implied by the slurred groups. Generally, slurred notes are grouped in such a way as to provide emphasis on the beginning part of the slur, so it's helpful to stress the first 16th in each group. This emphasis (as opposed to stressing the 8th notes) will also help bring out the accents in the next section as the stress gets relocated to the end of the groupings on the 8th notes.

I follow the general rule of phrasing -- "Up is Up and Down is Down" at the outset by allowing each 2/8 group to relax in intensity as the phrase relaxes in pitch to the note B. In general, the places for crescendo are marked, except at the end. What the phrasing needs is a few more places for diminuendo to set the level low again. Otherwise, there are three crescendos in a row (one per line).

In the second line, measure 4 there is a small detail. Many editions have accents over the second E and the F#, but the score shows tenuti, just like those two bars later. I think the tenuti work better here, unifying and simplifying the interpretation.

Many bassoonists play an echo phrase in the second line to add more contrast to the solo. I prefer the echo to start on the second beat of the next to last bar of line 2. This way the echo coincides and reinforces the embellishment of the previous phrase (which starts on the fourth bar of line 2). Compare the last two notes of the 4th bar with the last four notes of the 8th bar of the line and you'll understand my reasoning. Also, then the first phrase and echo are complete phrases and not fragments.

Rubato should play a role in any interpretation of this solo. It's really boring to hear this played steadily at ♪ = 112! Push and pull of tempo can come in line 2 with the tenuto 8ths holding back and the 16ths moving forward slightly. The accented section before it can have a slightly faster tempo if desired as well. All deviations from a steady tempo should be subtle and only be used to reinforce harmonic changes and other expressive ideas.

As I said before, there are many other wonderful interpretations of this solo to be heard in recordings. The Reiner recording with Leonard Sharrow is a great place to start, but also listen to the New York Philharmonic with Yuri Temirkanov (Judy LeClair) and the recordings with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra (Schoenbach, Garfield) for inspiration.

Thursday, August 4, 2016

Scheherazade, Context Comment

Here is a comment submitted via email from a reader of this blog regarding the importance of knowledge of context when playing excerpts:

"As a former jury member of several auditions in the Vienna State Opera I can assure prospective candidates for a position with a major orchestra that the members of the jury instinctively recognize if the candidate has played the excerpt in performance, or, if not, if they are familiar with the orchestral context. Any indication that the candidate is playing a perfunctory exercise will disqualify them."

"As a former jury member of several auditions in the Vienna State Opera I can assure prospective candidates for a position with a major orchestra that the members of the jury instinctively recognize if the candidate has played the excerpt in performance, or, if not, if they are familiar with the orchestral context. Any indication that the candidate is playing a perfunctory exercise will disqualify them."

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Scheherazade, Context Part. 2

CONTEXT, PART 2

Towards the middle of the second movement of Scheherazade come three short cadenzas for the bassoon. First the clarinet performs these three cadenzas earlier in the movement.

Compare the introduction of the first clarinet cadenza with the first one for bassoon:

The insertion of a woodwind fanfare at L makes it necessary for the bassoonist to wait a bit longer than the clarinetist to enter. Like each successive cadenza, the fanfares become more elaborate with each iteration.

Knowledge of context in these passages is most important at the end of each cadenza.

The first and second cadenzas end with a restoration of the tempo (♩ = 72).

It's a small point, but it's good to play the end of the cadenzas strictly in tempo:

This includes playing the triplet in time and cutting off the D on the rest and not holding it longer. The F should always be accented and lightly articulated to help the accent and the second D should be articulated. A diminuendo towards the D will help bring out the accent and the new tempo's downbeat.

The third cadenza ends in much the same way as the solo at the beginning of the movement -- with a pickup played in the tempo of the next section:

Like the first solo, there's another held dotted 16th D. The C# that follows should be played in the new tempo.

To finish, I like to use a "long" C# fingering for emphasis. Using the "short" fingering may cause the note to back up at "ff".

Next, I'll examine how to build interpretations for the solo and the cadenzas of the second movement.

Towards the middle of the second movement of Scheherazade come three short cadenzas for the bassoon. First the clarinet performs these three cadenzas earlier in the movement.

The insertion of a woodwind fanfare at L makes it necessary for the bassoonist to wait a bit longer than the clarinetist to enter. Like each successive cadenza, the fanfares become more elaborate with each iteration.

Knowledge of context in these passages is most important at the end of each cadenza.

It's a small point, but it's good to play the end of the cadenzas strictly in tempo:

The third cadenza ends in much the same way as the solo at the beginning of the movement -- with a pickup played in the tempo of the next section:

Like the first solo, there's another held dotted 16th D. The C# that follows should be played in the new tempo.

To finish, I like to use a "long" C# fingering for emphasis. Using the "short" fingering may cause the note to back up at "ff".

Friday, July 29, 2016

Scheherazade, Context, Part 1

CONTEXT

In the second movement, The Story of the Kalendar Prince, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote two extended bassoon solos.

The first solo comes at the beginning of the movement, right after the violin cadenza with harp accompaniment.

In order to form an interpretation of this solo which capitalizes on its expressive possibilities in such a way that the listener can fully appreciate them, an understanding of the solo's orchestral context is essential.

The Beginning

There are two things to note from the score about the beginning of the bassoon solo:

Therefore, it's helpful and expressively important to start with a full, resonant tone -- including the G grace note. I believe the phrase should relax in intensity to the B in bar three, so starting with a full sound also gives you a better chance for an expressive shape to the opening bars. In this solo, "Up is Up and Down is Down"* is a good maxim.

The Middle

After the beginning, projecting a solo sound is easy, given the light accompaniment of the four-part bass line. It is gratifying to play a solo like this which gives you opportunities to show the beauty of the bassoon's intimate nature along with its noble full-throated side.

By following the bass parts above, you can see that the harmonic motion is static for several bars. Notice where the chord changes occur (circled). By broadening at these points, you can enhance the new harmony underneath and allow the music to breathe. Breathe literally, too, as these chord changes happen near traditional breathing points for the bassoonist.

In order to bring out the seamless quality of this musical story telling, I strive to make my breathing as unobtrusive as possible. The phrases are like a chapters you weave together into a story in order to keep the constant attention of the listener.

Thus, when you do breathe, try to leave the last note before the breath with a rounded, resonant tone, breathe quickly and re-enter at the same intensity at which you left the sound. It helps to broaden a bit just before breathing. This buys you time for the breath without adding the perception that you've added beats to the measure.

The End

The harmonic motion speeds up, adding tension to the end of

the passage. Rimsky-Korsakov adds a ritard assai at the very end. Playing with a broad sense of time and an intense sound allows the final events to

unfold gracefully.

In the second movement, The Story of the Kalendar Prince, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote two extended bassoon solos.

The first solo comes at the beginning of the movement, right after the violin cadenza with harp accompaniment.

In order to form an interpretation of this solo which capitalizes on its expressive possibilities in such a way that the listener can fully appreciate them, an understanding of the solo's orchestral context is essential.

The Beginning

- The bassoon solo starts right after the violinist finishes on a very high note.

- The harp rolls a full chord on the downbeat of the measure in which you enter.

Therefore, it's helpful and expressively important to start with a full, resonant tone -- including the G grace note. I believe the phrase should relax in intensity to the B in bar three, so starting with a full sound also gives you a better chance for an expressive shape to the opening bars. In this solo, "Up is Up and Down is Down"* is a good maxim.

The Middle

By following the bass parts above, you can see that the harmonic motion is static for several bars. Notice where the chord changes occur (circled). By broadening at these points, you can enhance the new harmony underneath and allow the music to breathe. Breathe literally, too, as these chord changes happen near traditional breathing points for the bassoonist.

In order to bring out the seamless quality of this musical story telling, I strive to make my breathing as unobtrusive as possible. The phrases are like a chapters you weave together into a story in order to keep the constant attention of the listener.

Thus, when you do breathe, try to leave the last note before the breath with a rounded, resonant tone, breathe quickly and re-enter at the same intensity at which you left the sound. It helps to broaden a bit just before breathing. This buys you time for the breath without adding the perception that you've added beats to the measure.

The End

Knowledge of the context becomes most important when finishing this solo. There is a lot going on in the last few bars. By two bars before A I've reached the most expressive, fullest sound in the solo. In the next bar I begin the process of handing the solo off to the oboe.

The conductor re-enters the picture at this point to assist in the hand off. The ritard assai, along with serving an expressive function, gives the conductor and everyone who enters at A a chance to get ready to play.

Therefore, the D dotted 16th note in the last bar of the solo (last circled beat above) becomes the pivot point from one section to the next. This may be the longest dotted 16th note in the literature!!

You will see two beats from the conductor during this little note! One beat when you first play it to help the uppermost bass line move with you, and another to help you move from it to the C# and to give a pick up to those that enter at A.

Because the next section is in strict time and no longer flexible, the last two notes of the solo must be played in the NEW tempo: ♪=112. The need for the conductor and other musicians to start predictably

takes away any freedom you have here. In effect, the ritard assai only applies up to the famous D dotted 16th note.

Played as an Excerpt

In order to play this passage convincingly as an excerpt (in an audition, for instance), the performer must play with a sense that there is an imaginary conductor and orchestra in accompaniment. Younger, less experienced players who show their understanding of the context of this solo when performing it can ease the minds of those listening who may otherwise question their slim resumes and lack of experience.

Coming Next

In my next post, I'll examine the context of the three bassoon cadenzas that follow later in the movement.

* An expression used by oboist, John Mack to indicate phrasing in which a higher pitch is more intense than a lower one.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)